Farming Pure Ceylon Tea

Farming pure Ceylon Tea, requires skills and patience passed down through generations. Ceylon tea dominated the black tea markets through the 1990's at which time world-wide competition and the organic movement disrupted the Sri Lankan tea industry.

Young farmers questioned these practices with new hands-on skills and data-based decision tools. These entrepreneurs strive to bring sustainability to the plantations, workers and businesses themselves.

As worldwide customers become more concerned for their health, farmers health and environmental stewardship, Sri Lankan farmers are taking major, historic leaps to change both the tea farming culture and farming techniques.

“Pure” means farmed and processed in Sri Lanka. The tea may be organic or conventionally grown. “Organic” means both natural and "as defined in law by the National Organics Board in the USA". Our tea is pure and organic.

It's important to begin our discussion about farming pure Ceylon Tea by talking about:

- Tea growing regions in Sri Lanka

- Conventional farming practices

- Farming Organic Loose Tea

- How the Tea is Manufactured

- The Final Steps of Organic Tea Production - blending organic herbs, fruits and spices.

Farming Pure Ceylon Tea - The Growing Regions

Country of Sri Lanka (Ceylon)

Country of Sri Lanka (Ceylon)From the national loss of the coffee industry, due to the “coffee blight”, the first commercial tea plantation was introduced by the Scottish planter James Taylor in 1867 with seeds and plants from China. Tea knowledge has been passed down from generation to generation.

Sri Lanka is the fourth largest tea producer in the world and the largest producer of black tea. Sri Lanka produces more than 320,000 metric tons of tea yearly and is one of the top three tea exporters in the world.

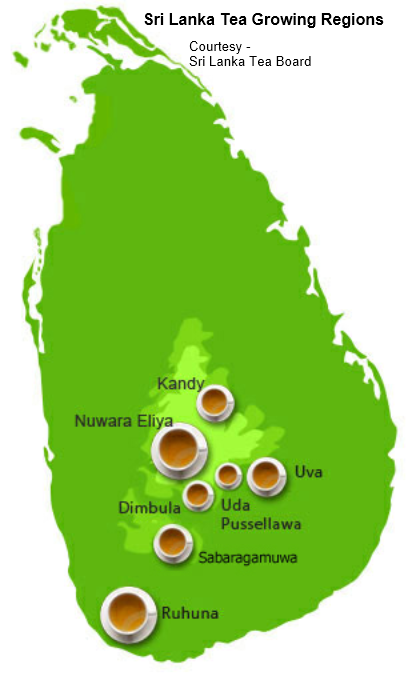

The tea varies in taste by growing region. Though farming pure Ceylon tea methods are similar across regions, the microclimates of each region, including elevation, temperature fluctuations, rainfall and intensity, direct sunlight exposure and wind, create teas with vastly different characteristics.

Three elevations also separate the tea characteristics, low-grown (up to 2,000 feet), medium-grown (about 2,000 – 4,000), and high-grown (above 4,000 feet). Additionally, the herbs, spices, and fruits grown in these regions, to be blended with the teas, vary in taste by region as do tea processing and tea blending. The compared characteristics are typically taste, the color of infused liquid (liquor), and aroma. These characteristics do not apply to green teas, only oxidized teas.

Uva Location of Embassy House Tea Blends© - Organic Farms

Location: Eastern slopes of central mountains

Elevation: High grown

Taste: Pungent, oak like tannins

Liquor: Amber to dark brown

Aroma: Exotic

Dimbulla

Location: Western slopes of central highlands

Elevation: High-grown

Taste: Delicate to strong

Liquor: Golden orange

Aroma: Light with jasmine

Nuwara Eliya

Location: Eastern slopes of central mountains

Elevation: High-grown

Taste: Smooth

Liquor: Light yellow orange

Aroma: Delicate minty bouquet

Uda Pussellawa

Location: Between Uva and Nuwara Eliya

Elevation: High-grown

Taste: Tangy

Liquor: Bright orange with a pinkish hue

Aroma: Subtle rose

Kandy

Location: Mid country

Elevation: Medium-grown

Taste: Delicate to pungent

Liquor: Bright copper

Aroma: Mild cypress bouquet

Ruhuna

Location: South edge of Sinharaja rain forest

Elevation: Low-grown

Taste: Sweet and coarse

Liquor: Dark brown to chocolate

Aroma: Exotic

Sabaragamuwa

Location: Southern part of island

Elevation: Low-grown

Taste: Smooth, mellow

Color: Dark yellow brown

Aroma: Sweet caramel

Ceylon Tea - Conventional Farming Practices

Like early agriculture in the United States, farming pure Ceylon tea in Sri Lanka started as organic in the mid 1800’s, moved to industrial agriculture during the 1940’s to late 1980’s and is now reinventing itself as farmers are re-learning the relationship of “growing the soil” first and the plants will follow. Growing organic tea sustainably is necessary for the industry to survive.

Like all farmers around the world, Ceylon tea farmers were and remain curious about the life cycle of their plant Camellia sinensis. "How can I make my crop more drought tolerant, more robust, able to grow faster and able to resist disease and ultimately more profitable." Research institutions like the Sri Lanka Tea Research Institute also ask and research these questions.

Initial Plantings -

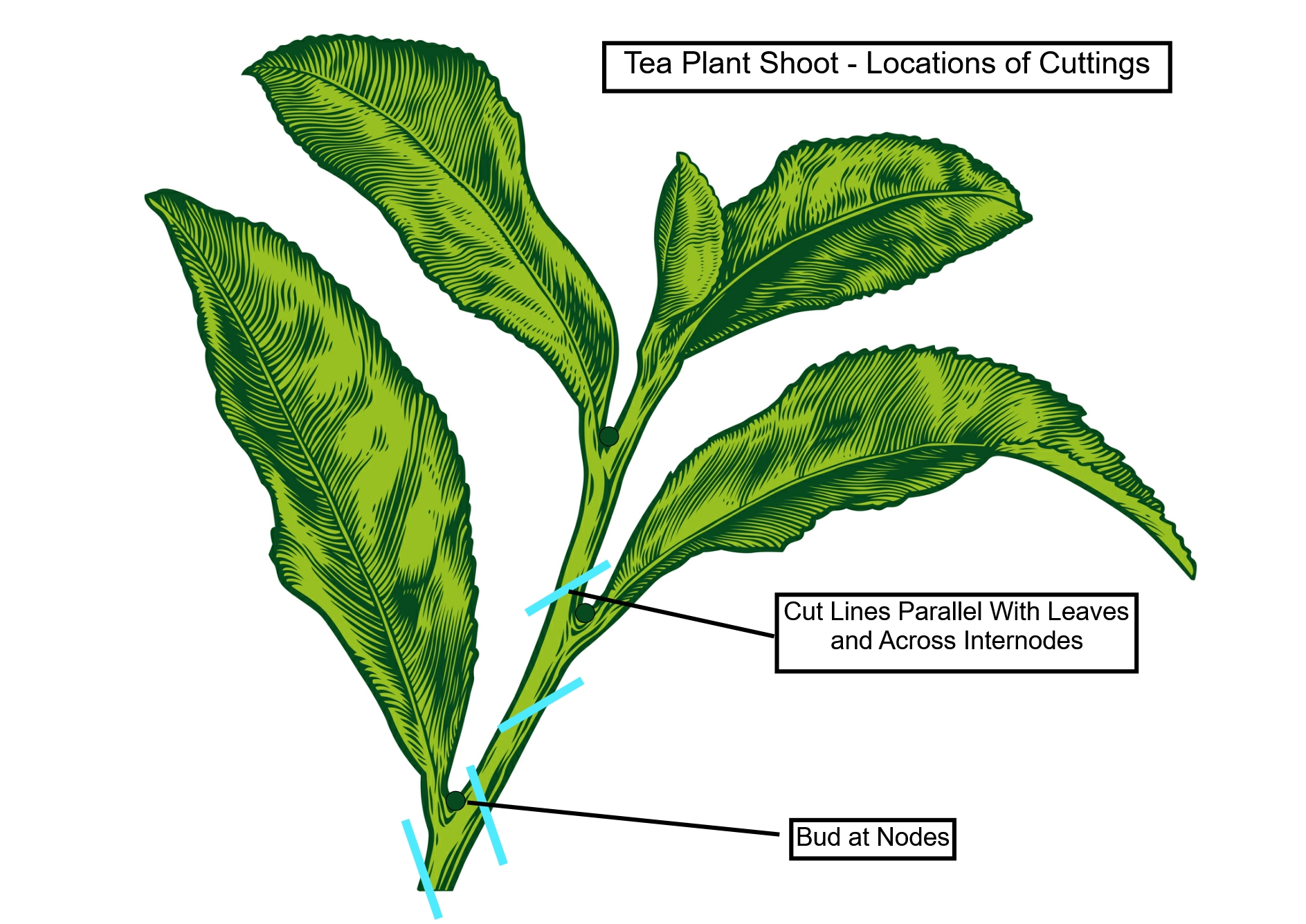

Farmers employ two methods, planting seeds from plants with desired traits and planting cuttings – taking stems from mature plants and replanting in the soil inside a nursery.

Seeding requires little upfront money but produces plants with unpredictable traits requiring more hand labor during the first three years. Plants may vary genetically and have undesirable traits. This method is losing favor.

Cuttings require much upfront labor and a nursery but produce a uniform plant which requires much less hand labor during the first three years. Cuttings, when planted, reach maturity about 18 months quicker than seed originated plants.

Farming pure Ceylon tea plants with specified traits is as much art as it is science.

Ceylon Organic Tea - Shoot Cuttings Locations

Ceylon Organic Tea - Shoot Cuttings Locations Ceylon Organic Tea - Mature Cuttings Ready For Hillside Planting

Ceylon Organic Tea - Mature Cuttings Ready For Hillside PlantingPreparation -

In preparation for planting, the land must be surveyed, ‘lined’ to mark the future position of each bush, drained and ‘holed’ to receive the plants. Proper drainage is vital; the ideal is a clean runoff with a minimum of erosion.

As in the United States, controversy exists over government mandates on private land use.

Clearing -

Sloping hillside is cleared of many but not all trees and overgrowth. The heavy timber, often valuable, is removed and the remaining cutting is burnt off, the resulting ash helping fertilize the soil. Some shade is beneficial for new plants. Clear cutting has the lowest upfront costs especially for small farms but increases costs over time with regard to soil erosion and upkeep of soil.

Conventional Tea Farming - Clear Cut Hill Side

Conventional Tea Farming - Clear Cut Hill SidePlanting -

As explained seeding has unpredictable results. Cuttings are preferred to maintain genetic purity for desired traits. The traditional pattern of farming pure Ceylon tea, with bushes arranged in geometrical clusters, was superseded in the 1960's by contour planting that closely follows the line of the hillside. Trees are planted amid the tea to provide partial shade and further control soil erosion.

Conventional Tea Plantation - Central Highlands

Conventional Tea Plantation - Central HighlandsWeeding -

Early planters weeded their fields clean, losing tons of topsoil with every shower of rain. This debate continues in the United States regarding till or no-till farming. Sir Lanka encourages farmers to remove weeds that can harm the tea. The balance, form root networks that stop erosion. However, topsoil loss remains a national problem as it causes water pollution and lowers profitability for the farmers as they lose valuable top soil.

Fertilization -

Sri Lanka allows the use of synthetic fertilizers and pesticides. Use is decreasing as farming pure Ceylon tea moves to sustainable production increasing yields and decreasing costs.

Pruning -

Tea-bushes need periodic full pruning. Pruning, which begins before the plant is mature enough for plucking, is repeated every couple of years after that, causing the bush to grow horizontally instead of vertically. Even with a special knife, pruning is a strenuous and difficult manual operation that resists automation. Human skill is an essential part of the process.

Plucking -

Harvesting plants at peak taste is year round but varies by elevation, climate and calendar year. The pluckers harvest the two tenderest leaves and the ‘bud’ that grow at the very top of every stem. Less optimum plucking results in coarser tea material and ultimately in poor-quality tea.

Pluck Two Tender Leafs and One Bud

Pluck Two Tender Leafs and One Bud Uva Highlands - Early Morning Plucking

Uva Highlands - Early Morning Plucking